Discussion Paper: Understanding Biodiversity Dependencies

Through exploring the interaction of tourism/human activities and biodiversity, this paper identifies blockages and restrictions in our ability to understand and manage human-wildlife conflict. Without humans coming into contact with biodiversity, they are unlikely to place any value on it, and yet, it is the coming into contact with biodiversity that causes negative impacts. This paradox can only be solved through a substantial shift in our ability to perceive complexity in our relationship with biodiversity. This has a direct impact on your organisation’s ability to reduce or avoid negative biodiversity impacts and begin building positive impacts in the future.

Why look at tourism?

Tourism is an amalgam of sectors, drawing on a broad range of products and services to deliver curated experiences throughout the world. Sitting atop of the economic sector hierarchy, tourism engages with many types of commercial activity, often unrelated and distinct from the trading entity. Reliance on extensive value chains reduces the operational cost-base, with particular dependencies on natural capital (biodiversity and pristine ecosystems) and cultural-historical resources, all of which are pre-existent and are available at little or no cost.

Accordingly, the nexus between tourism, human activities, and biodiversity is a complex interplay that has profound impacts on our planet. While tourism can be a tool for conservation of natural resources and indigenous communities by generating awareness and funding channels, it also poses significant threats through habitat destruction, pollution, and uncontrolled disruption. Human activities associated with tourism such as infrastructure development, waste generation, and resource consumption can exacerbate these threats, leading to large scale biodiversity loss and ecosystem degradation.

Conflicts are common

Human-wildlife conflict arises from the interaction between humans and biodiversity, particularly in areas where wildlife populations overlap or adjoin with human settlements or tourist activity sites. This conflict can result in property damage, crop loss, livestock predation, and even threats to human safety, leading to negative perceptions of wildlife and retaliatory killings. Finding sustainable solutions to human-wildlife conflict is crucial for promoting coexistence and ensuring the conservation of biodiversity.

Resolution of human-wildlife conflict requires a multi-faceted approach that considers the needs and perspectives of local communities, tourists, and wildlife populations. This may involve implementing measures such as habitat protection and restoration, wildlife corridors, fencing, early warning systems, compensation schemes for affected communities, and eco-friendly tourism practices. Community engagement and education are also essential for fostering understanding and tolerance towards wildlife and promoting sustainable livelihood options that reduce dependency on natural resources.

How to Understand Biodiversity Dependencies?

There is little point in directly asking the tourism sector about its biodiversity impacts and approach to reconciling human-wildlife conflicts – you’ll simply draw a blank. Much like the vast majority of business struggling to cope with sustainability and ESG reporting, the question of biodiversity impacts leaves the majority dumbfounded. Of those who can offer insight, they generally come from a strongly nature-sensitive background and have built an atypical organisation with little in common to standard commercial practices.

So, how to gain insight on the management effectiveness and perceived value and impacts of biodiversity? I conducted a survey of people who live in or near biodiversity areas, my rationale being that they see and must live with various viewpoints, often without vested interests. Local communities commonly bear the brunt of both human and wildlife problems, while being disenfranchised by both tourism and biodiversity management.

Biodiversity Survey Findings

During April and May 2024, the survey was to better understand individual and community dependencies on biodiversity and their perspectives regarding frameworks influencing biodiversity-community risks and opportunities. Respondents from Australia, India, Kenya, Nepal, South Africa, Switzerland, United Kingdom, United States provided information about 17 biodiversity areas.

Despite large variances in the size, resident and nearby populations, economic costs and benefits relating to biodiversity areas there was a very high degree, in fact almost universal alignment, of key issues:

Contributions to…

- biodiversity by community = Low to Moderate

- biodiversity by visitors = Low to Moderate (and more than community)

Financial Value to…

- biodiversity to community = Moderate to High

Non-financial value of…

- biodiversity to community = Moderate to High (and more than financial)

Wildlife interactions…

- most commonly perceived as “Occasional to Frequent”

- leading to feelings of Low to Moderate concern regarding human-wildlife conflicts

- 65% of respondents believe conflict are non-existent or rare

- 35% of respondents believe conflict are common, either significant or serious

Community engagement…

- with management plan and planning process is most commonly sporadic (88%)

- livelihoods generated relating to the biodiversity area are only a ‘few’ to ‘some’ (82%)

Universally, biodiversity management plans only focus on control mechanisms.

Governance is considered a problem in 88% of biodiversity areas with…

- 5% having multi-participatory process and responsibility sharing

- 83% having no or intermittent assessments of management practices

- 94% having poorly managed and/or unlinked cost/benefit distribution approaches

- 17% have biodiversity audits that include community assessments

Overall, survey responses characterised the broader paradoxes and contradictions of the human-biodiversity relationship, which are often in conflict, considered to be costly with low community buy-in, where the primary value is for ‘others’, resulting in dysfunctional management systems. Survey responses suggest the following mindset attributes:

- Biodiversity is more appreciated by social elite (tourists) rather than locals.

- Biodiversity is valued more in non-financial terms than financial.

- Relatively low fear of biodiversity, despite occasional to frequent interactions.

- Biodiversity is seen as an unpredictable commodity that must be controlled.

- Community engagement is often avoided by biodiversity managers.

- Biodiversity managers are often considered less than capable.

The biodiversity paradox is clear: we use it to value it, but by using it we destroy it.

Conservation vs Transformation

Our collective approach to biodiversity is rooted in nineteenth century values, when the first national parks were created to protect and preserve. The control mechanisms humans create often have little in common with nature’s own management systems, although there are efforts to realign them. Ironically conservation remains the priority, which of course, is impossible when our use unavoidably changes the nature of nature.

A complicating factor is our human tendency to make things simple. Nicely linear, nice and tidy. Nature isn’t linear, nor are we come to that, so trying to create linear, or even circular management systems for biodiversity is very unlikely to work. This conceptual myopia roots our human perspective in human solutions. When what we need is a more than human approach that can embrace complex positive and negative networks of impacts. In short, we need to transform our thinking to be able to really understand biodiversity.

The real conflict is in us

We are as much part of biodiversity as the wildest corner in the furthest sanctuary. To address this paradox of valuing biodiversity while minimising negative impacts, a paradigm shift is needed in how we perceive and interact with nature. This shift involves recognising the intrinsic value of biodiversity beyond its instrumental benefits to humans and acknowledging our interconnectedness with the natural world. By fostering a deeper sense of empathy, respect, and stewardship towards biodiversity, we can promote a more sustainable coexistence that benefits both ecosystems and human well-being.

Our dominant paradigm of Production-Protection sees biodiversity from a perspective of resource extraction and manipulation, controlled by biodiversity managers, to conserve value that is the feedstuff of tourism. We must transcend this approach to embrace multiple perspectives, human and non-human, that has room for a wealth of paradoxes and contradictions, each contributing to shared wisdom. Indigenous peoples throughout the world are very good at this!

Where do you start?

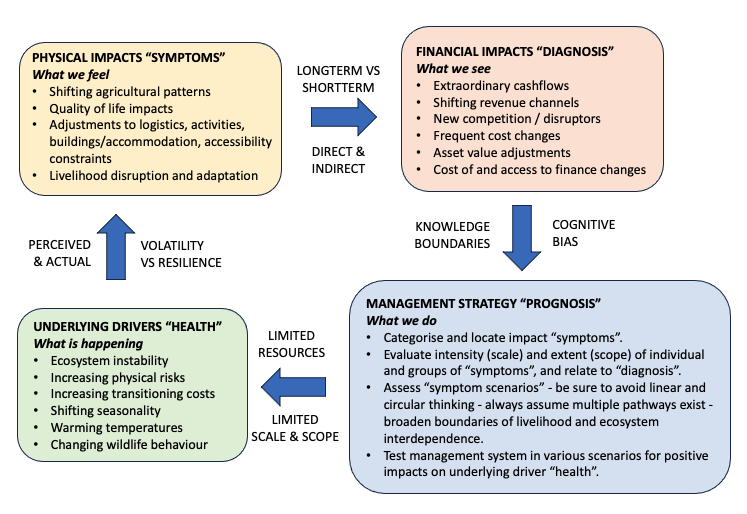

Let’s use an analogy, we’re sick and we go to the doctor. Often, our approach to identifying biodiversity impacts is vague, we feel that there are changes and issues, but we don’t have clear data or evidence. We’re experiencing symptoms, but we’re not really sure how long we’ve had them, nor what life was like before we had them. But when you talk to the doctor, they want to know all the symptoms, they need to understand as much as possible about what you are feeling. They are conducting a materiality assessment.

As part of the assessment the doctor will ask you to describe the impacts, the things that you see happening. This process categorises and prioritises what we feel into more and less relevant impacts. Once all the information has been analysed, filtered and repackaged your doctor will provide a prognosis – your symptom management plan – that must be applied in a particular way to drive positive impacts and you back to a healthier life. This approach isn’t going to ensure that we are healthy forever, but it will get us into some healthier habits and that’s a very good start, especially if you need to produce an ESG report!

But is there profit in it?

Yes, if we want to minimise exposure to new pathogens

Yes, if we want to effectively manage our dependencies

Yes, if we are to have a clear planetary rejuvenation and reparation pathway

Yes, if we still want to see wildlife in the wild.

Achieving true sustainability requires a holistic, fully integrated approach to biodiversity that balances conservation goals with socio-economic development and cultural preservation. Just like we approach our own health and wellbeing. This involves first addressing the limitations of our mindset and then identifying the underlying drivers of biodiversity loss such as overexploitation, habitat destruction, climate change, and unsustainable land use practices. By promoting responsible practices, supporting community-based conservation initiatives, and fostering partnerships between stakeholders, we can work towards a more harmonious relationship between humans and biodiversity that ensures the long-term health and resilience of our planet’s ecosystems.

Assessment methodology and reference material:

- Robin Boustead, 2024, Online survey conducted April-May 2024.

- Broadly based on the TNFD LEAP approach.

- Neil H. Carter and John D.C. Linnell, 2023, Building a resilient coexistence with wildlife in a more crowded world, PNAS Nexus, 2023, 2, 1–8. doi.org/10.1093/pnasnexus/pgad030

- Robert Fletcher, Kate Massarella, Katia M.P.M.B. Ferraz, Wilhelm A. Kiwango, Sanna Komi, Mathew B. Mabele, Silvio Marchini, Anja Nygren, Laila T. Sandroni, Peter S. Alagona, Alex McInturff, 2023, The production-protection nexus: How political-economic processes influence prospects for transformative change in human-wildlife interactions, Global Environmental Change #82. doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2023.102723

- Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations (FAO), 2024, Information brief: The wildlife–livelihoods–health nexus: challenges and priorities in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok. org/10.4060/cc9861en